Last year, at least 90 percent of the student body participated in cooperative education before graduating. The off-campus, professional-level employment aligned with their academic interests and allowed students to work six months up to three times during their college career.

It also helped graduates land jobs in their chosen career field as 44 percent of 2012 co-op participants were offered jobs by former co-op employers.

“Drexel students are in a unique advantage because they graduate with about 18 months of professional experience thanks to their co-op jobs,” said Peter J. Franks, vice provost for career education at Drexel. “As a result, 92 percent of the class of 2012 was either employed in college labor market jobs, enrolled in graduate school, or entered the military.”

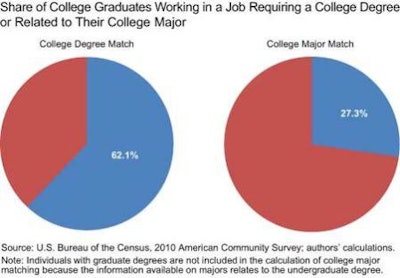

In 2010, a Federal Reserve Bank of New York study found that, though more than 62 percent of jobs required a degree, only about 27 percent of graduates worked in a field closely related to the major. Such research, which does not include graduate school students, is becoming increasingly more important in conversations about the value of a higher education.

As college tuition costs rise, more students, parents and taxpayers are asking institutions to show a return on the financial investment. They are calling for more data to assess whether a college education can deliver the high-paying, professional positions graduates seek in their chosen career fields.

“Institutions need to be nervous because more and more people want to know about the economic value of the education,” said Anthony P. Carnevale, director and Research Professor of the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. “Colleges never had to be accountable. Now, if you’re a for-profit college, you have to demonstrate that the program gives people the skills to get a job to pay back the loan.”

In May, a bipartisan group of senators and representatives introduced legislation that will arm students and parents with better data to make informed decisions. The Student Right to Know Before You Go Act aims to make higher education value and outcomes information more transparent. It will merge state and school data about graduation rates, job placement rates and a graduate’s ability to pay back loans online where it can be easily accessed.

“There’s no question that everyone needs access to higher education, but it’s time to bring value into the equation,” said Senator Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) in a press statement. “College is usually one of the most important and expensive investments people make in their lifetime. This bipartisan legislation would allow people to understand where they can expect their educational choices to take them in the real world.”

In the real world, the number of occupations exceeds the number of degree options, so students need transferrable skills. Human resources and career placement professionals recommend that institutions equip students with business and life skills that prepare them for different occupations and various areas of life.

“A lot of jobs don’t require someone to be an expert; they require you to be hard working with a great attitude who can get it done,” said Tom Darrow, founder and Principal of Talent Connections, an Atlanta staffing firm. “A lot of other jobs need a mix of competencies and skills, and there’s not a specific degree to do that.”

Changing careers will also become a constant for the present generation—with up to nine careers expected in their lifetime, said career coach J.T. O’Donnell. Half of tomorrow’s career options may not exist today, she added, so being flexible will prove valuable. Students will need universal skills that can grow and adapt as the world does.

College Career Service Centers can help equip students for the changing and demanding workforce and bridge the gap between academic and career success. The centers vary widely in terms of staffing and digital resources, but generally outline the steps students should take and offer training in business communication, resume writing and presentation skills. They can also provide information about internships and co-ops that give student valuable work experience.

“Students are going off to college and being advised to get a degree, but they’re not doing enough internships and getting the experience to translate into the work field,” said O’Donnell, founder and CEO of Careeralism.com. “They are graduating but considered professionally immature.”

O’Donnell recommends that schools invest more funding in the career centers, especially in technology, and develop mandatory curriculum that includes career assessments and business skill development. They should also require internships or work experience before graduation.

“College teaches you discipline and how to study, how to think, plan, and all those things,” said Darrow, a board member of the Society of Human Resource Management Foundation. “That’s part of getting a degree. It is and always will be an important thing to do.”