In this important and timely examination of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), Dr. Joseph L. Jones, a political science professor at Clark

The book’s architecture is carefully constructed around ten interconnected themes, each building upon Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois’s foundational writings on Black education. Jones begins by challenging the very designation of “historically Black,” arguing that this federal label has inadvertently trapped these institutions in a cycle of dependency and identity crisis. He methodically unpacks how this manifests in various aspects of institutional life, from leadership and curriculum to campus culture and financial sustainability.

Some of the book’s most compelling sections deal with what Jones calls “misleadership” at HBCUs. He describes presidents who rule like autocrats, boards of trustees who lack higher education expertise, and administrative practices that prioritize image over substance. His critique of “professional incest” – the recycling of mediocre administrators between institutions – is particularly scathing. Yet Jones speaks from experience, admitting his own past failures and complicity in these systemic problems.

The author’s discussion of academic standards and cultural dysfunction is equally unflinching. He shares powerful anecdotes about students who have been passed along without proper academic preparation, faculty who have abandoned rigorous standards, and administrators who perpetuate a culture of low expectations. His account of a student challenging his grading standards because “no other professor” had criticized his writing is both heartbreaking and illuminating.

Financial sustainability receives careful attention, with Jones detailing how dependency on federal funding and philanthropic gifts has created a precarious existence for many HBCUs. His analysis of tuition discounting practices and their impact on institutional stability is particularly insightful. The author advocates for radical transparency in financial matters and suggests innovative approaches to building financial independence.

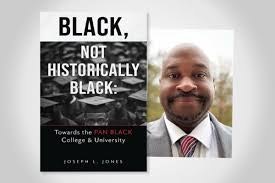

The book’s most original contribution is its vision of the Pan-Black College & University (PBCU) model. Jones envisions institutions that embrace Black excellence without seeking white validation, that connect African Americans to the global African diaspora, and that serve as models of social justice and equity. His criticism of diversity initiatives that mimic predominantly white institutions is especially pointed.

Jones’s exploration of respectability politics at HBCUs is nuanced and thought-provoking. He argues that these institutions must move beyond policing students’ dress, speech, and behavior according to white standards, instead fostering genuine respect for self and others within a Pan-Black framework. His discussion of how this plays out in everything from dress codes to protest politics is particularly relevant in our current moment.

The work’s limitations are few but notable. The focus on private HBCUs, while acknowledged, leaves questions about how these critiques and solutions might apply to public institutions. Some readers might also wish for more detailed implementation strategies for the PBCU model Jones proposes.