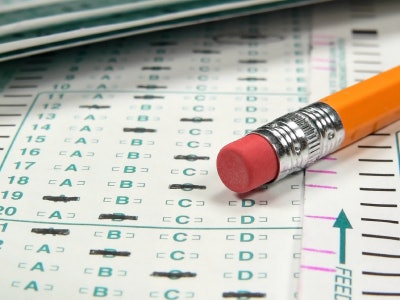

More than 700,000 high school dropouts take the General Educational Development exam each year.

More than 700,000 high school dropouts take the General Educational Development exam each year.

The new exam will have four parts and cost much more — $120, a fee that includes the book. It will also be computerized. And while few people outside the agency that administers the test have seen the exam, experts and adult education administrators say the earliest indications are that it will be more rigorous.

Some welcome the rigor, but others worry that the changes will discourage people from taking the exam. Historically, the number of test takers has declined in the year or two after the exam was adjusted; the pass rate has also dropped. Experts predict the trend won’t be any different this time. They worry that it would discourage many from pursuing some form of higher education and could impact enrollment at some higher education institutions, like community colleges and technical schools. They say this trend could be more pronounced among many minority groups. Approximately 50 percent of the test takers are people of color. Blacks and Hispanics make up about four-fifths of these exam candidates.

More than 700,000 high school dropouts take the exam each year. More than half of these examinees report that they take the exam because they want to pursue some higher education. But many critics have long charged that the GED lacks the rigor of the traditional high school diploma.

The changes to the exam are designed to heighten the standard, align it with the common core curriculum at traditional high schools and to better prepare students for college. More to the point, educators want the exam to reflect the learning and outcomes in regular school systems, says Dr. Jacqueline Korengel, director of strategic initiatives and GED administrator for Kentucky Adult Education, part of the Council on Postsecondary Education. Increasingly, she says, more jobs are requiring some postsecondary education. Organizers of the GED recognize this and have adapted the test to help prepare them for college.

But concern that these changes might have a deleterious effect on people of color — at least initially — lingers.

“I think it would mean that fewer people will be able to get that credential,” says Emily Hanford, a producer at American Radio Works, whose hour-long documentary on the GED is airing on public radio outlets. “The GED is disproportionately something that people from low-income and minority communities get. Low-income people and people of color are being disproportionately served by this test, and they are being disproportionately harmed by this test.”